Chapter 2 – Process Evaluation: Getting on the Right Track

Introduction

Process evaluation is the examination of SHSP management processes. The results identify successful practices; alert SHSP leaders, managers, and stakeholders to potential needs, weaknesses, and threats; and provide insights for overcoming those challenges and improving the process.

Purpose

Source: Cambridge Systematics, Inc.

Evaluation requires attention to SHSP outputs and outcomes, but also to the management of the SHSP. Conducting a process evaluation provides insight into a variety of SHSP program management elements, such as organizational structure; coordination; the use of data in determining emphasis areas, goals, objectives, strategies and actions; and the alignment of agency priorities.

Methods

Methods to assess SHSP processes will vary, but this section offers some potential methods used effectively by States.

Identify Process Evaluation Elements

The following elements should be assessed for a comprehensive process evaluation. These have been identified in the SHSP Implementation Process Model (IPM) as essential for successful SHSP implementation, but States can consider additional elements as well.

Source: PhotoDisc Inc.

- SHSP organizational structure;

- Multidisciplinary, multimodal collaboration;

- SHSP goal and objective setting methods;

- Data driven and evidence-based emphasis areas, strategies, and actions; and

- Aligned agency priorities.

SHSP Organizational Structure

Assessing the organizational structure for SHSP implementation provides information about how well it is performing. The organizational structure varies from State to State, but regardless of the form it takes, it should function to manage the entire SHSP process; from development and implementation to evaluation and measuring performance. Assessing the SHSP organizational structure helps determine if it is providing the support needed to manage the SHSP process. An example of an SHSP organizational structure is provided in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Example SHSP Organizational Structure

Source: Cambridge Systematics, Inc.

Key features of this structure include:

- An executive committee or leadership council composed of members who are leaders of departments and agencies, such as the department of transportation, the State Highway Safety Office (SHSO), public safety, statewide law enforcement organizations, licensing agencies, departments of health and education, and others.

- A steering committee or working group designed to represent not only the executive committee, but also the majority of partners.

- Multidisciplinary emphasis area teams composed of stakeholders from the safety community, as well as other interested partners, experts, and citizens. Some States also encourage local, tribal, regional, and district representation to provide additional focus for certain geographical regions.

- An SHSP program coordinator who is responsible for the overall day-to-day management of SHSP activities.

A review of the organizational structure should identify and document:

- How representatives are recruited. A State should review how they recruit representatives for the various SHSP committees and teams to determine if they have an active and successful process for reaching out to partners. For example, in some States, leaders of one or more of the key agencies recruit their counterparts from other agencies. In other States, the SHSP manager may hold one-on-one meetings with top-level executives to discuss their participation and identify incentives for their involvement. States also should determine if potential partners can easily contact and reach out to those already involved in the SHSP to express their interest in participating.

- Representation on various committees or working groups. A State should examine the representation on SHSP committees and working groups to determine if they are multidisciplinary and multimodal. Representation should include a broad range of stakeholders from key agencies and organizations.

- Access to leadership, resources, etc. States should assess the level of access the various SHSP committees and working groups have to top management and leadership. They also should consider if they have ample opportunities to keep leadership informed of SHSP progress, and gain their support in addressing challenges. Emphasis area teams should have access to steering or executive committee members as well as managers in their respective agencies.

- Meeting frequency and level of participation on SHSP committees, teams, and working groups. States should review the degree to which frequency and participation levels have met or changed from original expectations.

- The role and function of the SHSP

committees, teams, and/or groups. Use

the following questions to assess the roles

and functions:

- Does a committee (e.g., executive committee) oversee the SHSP effort? How often does it meet to assess progress, determine priorities, recommend course corrections, and address challenges? Does the committee appoint representatives to a steering committee or to working groups? Do these representatives have access to top-level executives and the ability to make decisions?

- Is a committee (e.g., steering committee) responsible for day-to-day SHSP implementation?

- Is a committee responsible for providing support to local and regional partners?

- Do the Emphasis Area Teams develop the performance measures, strategies, and action steps necessary for translating the goals and objectives of the SHSP into detailed action plans?

- Is there an SHSP program manager or coordinator who oversees the overall day-to-day management of SHSP activities (e.g., convenes, facilitates, and documents committees, working groups, emphasis area teams, etc.)?

- How do the existing roles and functions of the various SHSP committees and groups compare to original expectations?

A candid discussion among the committee and/or working group members can often identify the strengths and weaknesses of the organizational structure (e.g., multidisciplinary representation, leadership or access to leadership, etc.) and identify strategies for improvement. (Review the SHSP Implementation Process Model (IPM) for information about establishing effective executive, steering, and emphasis area teams.)

Recommended Actions

- Review the SHSP organizational structure to identify and document its format and functions(s).

- Examine the positions of persons serving on SHSP committees (e.g., steering and executive committees), as well as emphasis area and local/regional/district teams to determine their contribution to the SHSP process and access to leadership and resources.

- Review the schedule of SHSP leadership and committee meetings to determine if they meet as frequently as planned or needed.

- Review the SHSP organizational structure to determine the level of support provided to partners in local and regional coalitions.

- Review the role and function of SHSP committees, teams, and/or groups. Compare these current roles and functions with the expectations set at the beginning of the SHSP process.

Multidisciplinary, Multimodal Collaboration

Traffic fatalities and serious injuries involve multiple contributing factors which affect the mission and work of many disciplines and agencies. This highlights the need for multidisciplinary and multiagency approaches and is why the SHSP is required to involve the input of disciplines representing the 4 E’s of safety (engineering, enforcement, education, and Emergency Medical Services (EMS)). SHSP partners typically include the State Department of Transportation (DOT); the State Highway Safety Office (SHSO); departments of public safety (State police or patrol); health and education; Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program (MCSAP) managers; Federal partners (FHWA, FMCSA, and NHTSA); metropolitan planning organizations (MPO); local agencies; tribal governments; special interest groups; and others.

The various agencies and organizations involved in the SHSP bring unique and valuable perspectives to bear on the roadway safety problem. Their differing philosophies and problem solving approaches, however, can sometimes make collaboration challenging. Measuring the effectiveness of communication and collaboration among the disciplines and agencies can be difficult; however, it is important to know if the right people are at the table and if they are working together effectively.

Safety improvement also requires attention to the different roadway users and the interaction among them, e.g., passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles, trains, pedestrians, bicyclists, motorcyclists, transit users, and others. Communication, collaboration, and interaction among the disciplines and modes improve the potential for identifying and addressing issues, implementing programs, and assessing effectiveness. Each State’s SHSP leadership should assess the decision-making environment and encourage key agencies and individuals to be involved. The Champion’s Guidebook and IPM provide further detail for identifying the collaboration partners and processes.

The representatives that make up emphasis area action teams, task forces, etc., can be interviewed or surveyed to determine the degree to which multiple disciplines and modes are represented and collaborative arrangements are in place. These individuals can be contacted during regular monthly or quarterly meetings; however, input from less active stakeholders also is valuable. Often working group members are program managers rather than practitioners or field personnel. Interviews with field personnel will strengthen the evaluation’s validity and lead to more robust results. States should identify the interviewees depending on the SHSP emphasis areas, strategies, and action plans. Typical interview or survey candidates include:

- Project and program directors;

- State and local law enforcement participating in SHSP-related campaigns;

- HSIP, SHSO, and MCSAP staff;

- Transportation planners at the State, regional, and local levels;

- County, regional, and local traffic and safety engineers;

- Other State, regional, and local safety professionals (from Departments of Health, Departments of Education, etc.); and

- State and local elected and appointed officials.

When reviewing collaboration processes, States should ask:

- Does a basic foundation for effective collaboration and a process to support collaborative efforts exist? For example, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) can be a useful tool for institutionalizing the collaborative process. MOUs also help with the implementation of strategies and build sustainability and accountability. As stakeholders change and new partners come on board, commitment on the part of all agencies can be reaffirmed by updating the MOU. What mechanisms are in place to support collaboration?

- Does collaboration result in multidisciplinary safety decisions that are reflected in other plans and programs? Other safety and transportation plans, such as the HSP, HSIP, the CVSP, the long-range transportation plan (LRTP), statewide and regional transportation improvement programs (S/TIP), and other planning and programming documents should be consistent with the SHSP goals, objectives, and strategies as appropriate to their missions, regulations, requirements, and stakeholders. Conversely, SHSP managers and stakeholders should consider the relevant goals, objectives, and strategies in the other plans. Has collaboration resulted in this level of coordination and alignment?

- Are the vision, mission, and goals of the SHSP clearly and continually communicated to all partners and stakeholders? Identify formal and informal communication mechanisms for ensuring frequent and continuous information regarding the SHSP, such as regularly scheduled steering committee meetings, newsletters, retreats, etc. How effective are they?

Reviewing the status of SHSP collaboration should reveal if the SHSP process is truly multidisciplinary and multimodal. Collaboration should be evident not only in the SHSP development process, but also in the alignment of State safety priorities and plans and the implementation of SHSP strategies.

Recommended Actions

- Review the membership of the various committees, emphasis area action teams, task forces, etc., to assess the degree to which multiple disciplines and modes are represented and actively involved.

- Determine if mechanisms are in place that facilitate an active, efficient collaborative process, such as MOUs.

- Review the planning documents of the various agencies and safety partners to discern how well they reflect elements of the SHSP, such as the goals, objectives, and strategies.

- Determine if the SHSP vision, mission, and goals are clearly and continually communicated to all partners and stakeholders.

Goal and Objective Setting Methods

Evaluation in Action

Louisiana Uses Data to Set Annual SHSP Objectives

Louisiana uses data to set annual SHSP objectives for the reduction of traffic-related fatalities and serious injuries. The State adopted a goal to halve fatalities by 2030 and uses a baseline average of 2006-2008 fatality and serious injury data to calculate the rate of change necessary to achieve the 50 percent reduction. Louisiana regularly evaluates the plan’s effectiveness by using the annual number of motor vehicle-related fatalities and serious injuries as performance measures. The same metric is also used to track performance for each emphasis area and to indicate the number of countermeasures underway, completed, or not started. Louisiana bases the selection of SHSP emphasis areas on baseline data, which clearly defines the problem, the contributing crash factors, programs and projects with the greatest potential for improvement, and whether sufficient resources to implement proven countermeasures are available.

Establishing performance measures and setting transportation safety goals and objectives are becoming widely advocated practices in the U.S. and internation- ally. Evidence shows reductions in fatalities and fatality rates are positively correlated with setting measurable objectives (Gargett, S., Connelly, L.G., and Nghiem, S. (2011). Are we there yet? Australian road safety targets and road traffic crash fatalities, BMC Public Health, 11:270, 2011.). Objectives improve road safety by:

- Providing a way to measure program effectiveness;

- Steering programs toward implementation of proven effective road safety countermeasures;

- Motivating stakeholders to act; and

- Establishing a method for assessing accountability. (OECD and International Transport Forum. (2008). Towards Zero: Ambitious road safety targets and the safe system approach, Paris, OECD.)

The process evaluation should identify and assess the methods used to set SHSP goals and objectives. For example:

- Are data driven objective setting methods used, as opposed to aspirational goals?

- Are goals aggressive yet achievable?

- Are objectives specific, measurable, time bound, and realistic?

SHSP goals and objectives typically have a foundation in data analysis and broad political support. They should be aggressive yet achievable. Numerous methods are used to identify and set objectives, such as using historical trends, modeling, benchmarking, relying on expert judgment, collaborating with stakeholders, applying legislative mandates, adopting a national strategy or recommendation, or some combination of the above. One of the most commonly used methods is trend analysis, which is discussed in more detail below.

Using Trend Analysis to Set Ojectives

Often some form of trend analysis is employed to determine where the State will be if current trends continue. The anticipated effects of the State's efforts are then applied to the trend to estimate the impact and set SHSP goals and objectives.

To conduct a trend analysis, evaluators should chart a rolling average over time using three to five years of data. A rolling average chart provides a smoother line than a chart of individual data points, making trends more evident. These trend lines show what has occurred in the past and can then be extrapolated into the future to provide a sense of what might be expected if the trends continue. This extrapolated trend line becomes the baseline against which goals and objectives are set.

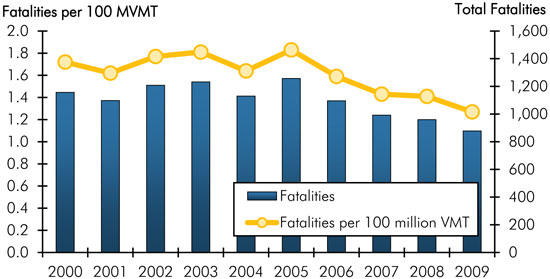

Figure 2 shows historical fatality data from Missouri. The bars show the actual number of fatalities from 2000 to 2009 while the line shows the fatality rate per 100 million vehicle miles of travel over the same time period. To conduct a trend analysis, this data would be projected into the future assuming no changes in current safety efforts. From this baseline, future goals and objectives are set.

Figure 2. Missouri Fatalities and Fatality Rates

Source: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. based on data from the Missouri Department of Transportation.

Trend analysis also can be conducted by emphasis area to show more precisely where safety improvements and degradations are occurring.

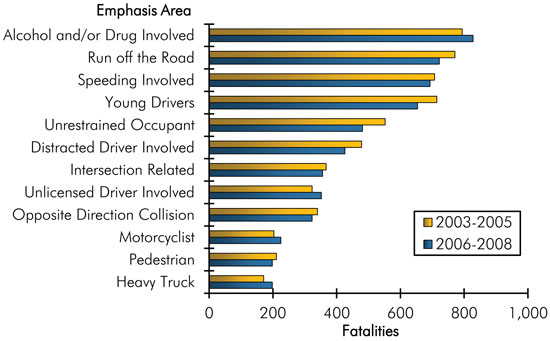

Figure 3 demonstrates another method for displaying historical data to set future objectives. These data show general trends for Washington State’s emphasis area and can help SHSP leadership identify which emphasis areas need greater attention. The horizontal bars show three-year total fatalities by emphasis area. The red bars show earlier years (2003-2005) and the blue bars demonstrate the most recent years (2006-2008). For example, the blue bar associated with Alcohol and/or Drug Involved Fatalities extends further than the red bar which means the number of fatalities is increasing rather than staying the same or improving. To conduct trend analysis for each of the emphasis areas, a State would track historical fatalities by emphasis area, set a baseline by projecting the resulting trends into the future, and set goals and objectives against the baseline.

Figure 3. Emphasis Area Chart (Dervied from Washington State SHSP)

Evaluation in Action

Virginia Uses Data to Identify SHSP Emphasis Areas

Virginia uses a data-driven process to identify emphasis areas for the SHSP. Stakeholders review the percentage of total traffic deaths and severe injuries attributed to each of the potential emphasis areas in the AASHTO SHSP. While crash factors are often interrelated and reflected in more than one emphasis area, the significant areas that Virginia’s crash data highlights are roadway departure, speeding, intersection crashes, and young drivers. These became the Commonwealth’s SHSP emphasis areas.

Source: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. based on data from Washington State’s Strategic Highway Safety Plan.

Recommended Actions

- Review the analysis methods used to set objectives. Are they data driven?

- Determine if objectives are specific, measurable, time bound, and realistic.

Data-Driven and Evidence-Based Emphasis Areas, Strategies, and Actions

Process evaluation helps States assess whether their efforts are data driven and focused in areas where documented safety problems exist, for both infrastructure and behavioral programs. Process evaluation also assesses whether the appropriate strategies and actions have been selected.

A data-driven approach to problem identification is critical because it provides the information and statistics needed to determine the most significant safety problems (emphasis areas) and select the appropriate performance measures. Using crash and other safety data to guide emphasis area selection helps direct resources to the areas of greatest need.

Evaluation in Action

Maine Uses Data to Select SHSP Strategies

Maine reviews crash, complaint, citation, injury, and emergency medical services (EMS) data, as well as observational and attitudinal survey data to inform the selection of SHSP strategies. The State collects crash and EMS data electronically and strong collaboration among State agencies facilitates effective data sharing and access, which results in excellent data quality and enables the stakeholders to uncover detailed information about traffic safety challenges. For instance, a review of the crash data revealed the need for further analysis of operating after suspension (OAS) data to filter out suspensions unrelated to driving behavior, such as failure to pay child support; hence it is difficult to link OAS strategies to crash outcomes. Therefore, Maine adopted a set of strategies in the SHSP to address the issue, such as develop a mechanism in the Maine Crash Reporting System to identify the reason an operator involved in a crash is suspended.

Process evaluation also should include a review of how strategies are selected. It is best to select strategies and countermeasures based on evidence from the research. These can be found in a variety of sources, including the NCHRP 500 Series (NCHRP: National Cooperative Highway Research Program), the FHWA Crash Modification Factors Clearinghouse, the Highway Safety Manual, Countermeasures that Work, and NCHRP 622: Effectiveness of Behavioral Highway Safety Countermeasures. If a new, promising, or innovative strategy with less research to support its effectiveness is identified, the strategy should be accompanied by an evaluation to validate its impact and justify future use.

Recommended Actions

- Review methods used for identifying safety problems and selecting emphasis areas. Determine whether safety data analysis was the primary input to problem identification and emphasis area selection.

- Determine whether the latest safety data and research was used to identify evidence-based strategies and actions.

- Identify strategies in the SHSP that may lack a preponderance of evidence of effectiveness. Determine if there was enough information or evidence (e.g., success in another State) to justify its use, or if an evaluation was conducted, or is planned, to validate the use of the strategy.

Aligning Agency Priorities

Another type of process evaluation measures shifts in agency priorities. Effective SHSP management leverages the resources of other transportation planning and programming activities. SHSPs are designed to be the umbrella or overarching safety plan for a State; hence, it is expected the partner agencies will begin to shift their priorities where appropriate to align with the SHSP goals, objectives, performance measures, emphasis areas, etc. Evaluation of these often subtle changes could be accomplished by examining the individual agency programs before and after SHSP implementation to identify programmatic and budgetary shifts in agency priorities, as well as changes to the safety decision-making culture. These would indicate a shift of institutional processes and practices to align with SHSP goals, objectives, and performance measures at agencies responsible for transportation safety.

Alignment should occur in the State’s: Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP); Highway Safety Plan (HSP):, Commercial Vehicle Safety Plan (CVSP); Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP); and the Statewide and Metropolitan Transportation Improvement Program (S/TIP). Alignment also should be evident in other transportation planning documents, such as pedestrian/bicycle plans, corridor plans, and freight plans among others.

Recommended Actions

- Review the HSP, CVSP, HSIP, LRTP, and S/TIPs to determine the degree to which they align with the SHSP.

- Review other plans, e.g., pedestrian/bicycle plans, corridor plans, local road plans, etc., to determine the degree to which their goals and strategies align with the SHSP.

Process Evaluation Activities

States can use a number of methods to collect process evaluation information. Examples include:

- SHSP Retreat or Group Exercise. The working group or steering committee holds a retreat or group exercise and devotes themselves to a candid discussion of the SHSP process. An experienced facilitator should be considered to keep the participants on topic and help the group work through areas of uncertainty or potential disagreement. The discussion should focus on accomplishments and identify opportunities for improvement. A retreat report should document the findings, follow up actions, and persons responsible for implementing the actions. Refer to the HSIP Self Assessment Toolbox for more ideas on how to format and facilitate this type of activity.

- Internal Evaluation. The SHSP Program Coordinator, with staff support, conducts an internal evaluation of the SHSP process. This approach depends on support from the State’s SHSP leadership.

- Objective Observer. An objective observer collects information through a survey and/or a series of interviews with working group members, safety stakeholders, top management, and others. The observer documents the findings and follows up with the interviewees to validate or clarify the findings and gather any additional information. The observer prepares a report for review by SHSP leadership, the working group, and other stakeholders.

- Peer Review or Exchange. A State hosts a peer review or exchange with one or more other States to present its SHSP process elements and methods. Together they identify strengths and weaknesses and the peer State representatives offer alternative methods to improve SHSP process effectiveness. Peer exchanges provide a good model for improving practice, as demonstrated by the State DOT research divisions which have been implementing this practice for many years. An important element is the involvement of an experienced facilitator with knowledge of the process and the subject areas who keeps the discussion on track and documents and reports the findings.

Recommended Action

- Review the possible methods to collect process evaluation information. Identify the pros and cons of each method.

- Determine and document the most appropriate method and the rationale for the selection.

Self Assessment Questions

Evaluation in Action

Rhode Island Peer Exchange Provides Help for SHSP Update

At the beginning of the SHSP update process Rhode Island hosted a peer exchange to learn from the experiences of Georgia and Maine. A focus of the discussion was tracking SHSP implementation and measuring SHSP effectiveness. Rhode Island would like to invest in data collection and analysis systems to accurately identify emphasis areas and track performance. Because data are central to the evaluation process, the State was interested to learn how peer States are addressing the issue of incomplete data. Georgia identified training for law enforcement personnel and the implementation of an electronic crash reporting system as critical for improving crash data accuracy and timeliness. Maine reported the benefits of their simple query format to perform crash data analysis on attributes recorded in crash reports, as well as the development of standard reports on topics such as motorcycle crashes and high crash locations to communicate the latest crash trends.

The following self assessment questions are designed to inform process evaluation. Answering “yes” to a question indicates the State has a well functioning SHSP process in that area of review. Answering “no” indicates improvements can be made.

- Is the SHSP process supported by an actively engaged organizational structure?

- Are top-level managers represented in executive committees or leadership structures/groups established for the SHSP?

- Are members of the executive or leadership group, the steering committee, the emphasis area teams, and other groups multidisciplinary and multimodal?

- Do members of the executive committee or leadership group have the decision-making authority needed to effectively support the SHSP process?

- Do members of the executive committee or leadership group assign persons with decision-making authority to the steering committee or working group?

- Are multiple transportation modes represented, and do they actively participate on the steering committee/working group and emphasis area teams?

- Has an SHSP program coordinator or manager been assigned? What percentage of this person’s time is dedicated to the SHSP?

- Do the leadership and working groups/committees meet as frequently as expected?

- Are emphasis areas supported by teams with engaged leaders?

- Are local/regional/district coalitions supported by the SHSP organizational structure?

- Are the necessary disciplines, modes, and agencies (representing the 4 E’s) engaged in SHSP decision-making and implementation?

- Do the stakeholders regularly collaborate on decisions that affect SHSP updates and implementation?

- Do the necessary stakeholders collaborate and jointly decide on SHSP goal and objective setting methods?

- Are data-driven methods, such as trend analysis, used to establish goals and set aggressive, yet achievable, objectives?

- Are objectives specific, measurable, time bound, and realistic?

- Is data analysis used to select the emphasis areas?

- Are the emphasis area strategies selected through an evidence-based process?

- Are promising and innovative strategies with less evidence of effectiveness accompanied by an evaluation?

- Have the various agencies and safety partners incorporated elements of the SHSP into their planning documents? (HSPs, HSIPs, CVSPs, LRTPs, S/TIPs, etc.)